Near-miss incidents: Crew transfer vehicles approaching wind turbines

- Safety Flash

- Published on 8 May 2015

- Generated on 16 January 2026

- IMCA SF 06/15

- 4 minute read

Jump to:

A Member has reported a number of recent near miss incidents involving the approach of small boats – offshore renewable industry crew transfer vehicles – to wind turbine towers.

In both incidents the vessels have become unattached from the boat landing and have then become dangerously close to hitting the monopile when taking avoiding action.

Incident 1

During personnel transfer onto the crew transfer vessel a wave caused the bow of the vessel to shift to the port side on the boat landing; the Master tried to correct the movement by altering the steering to the starboard side. A misjudgement caused the vessel to suddenly over-compensate and become even further off centre upon the boat landing. The Master then slewed the vessel around to starboard in order to realign upon the boat landing without the tide and wave influence (on the beam when in the transfer position). At this point the vessel became unattached from the boat landing. To avoid hitting the monopile, unable to reverse due to a following sea, the Master throttled forwards away from danger. The vessel passed approximately 2m from the boat landing.

Our member noted that if the Master knew he was about to make a significant steering alteration he should have informed the crewman first to allow him to safely evacuate the transfer platform before the movement began.

Our member’s recommendation was that if a crew transfer vessel moves significantly off centre of a boat landing, the Master should first instruct the crewman to remove himself from the transfer platform and tell him to order the technicians to STOP transfer and standby. Then the Master should pull the vessel away from the wind turbine and begin correct push-on again before recommencing transfer.

Incident 2

A crew transfer vessel was at work in marginal sea/weather conditions that were near to the limit of the vessel capabilities to transfer crew in a safe manner. The Master made the decision to attempt pushing onto a wind turbine boat landing in order to better assess the vessel’s movement. After a short while he quickly deemed the weather conditions too severe and decided to abort the procedure. When the Master put the jet controls into reverse to move astern, only one jet responded. Due to the high engine power being applied to hold the vessel in position against the boat landing, the vessel turned sharply to starboard in front of the boat landing. The Master instantly attempted to use the jog steer back up controls to avoid collision but this was unsuccessful; the port jet would not respond. Next the Master tripped the jet control isolators and re-booted the system. This time all was now working correctly and the vessel was driven away from danger and returned to shore without further problems. Again the crew transfer vessel came within two metres of colliding with the monopile.

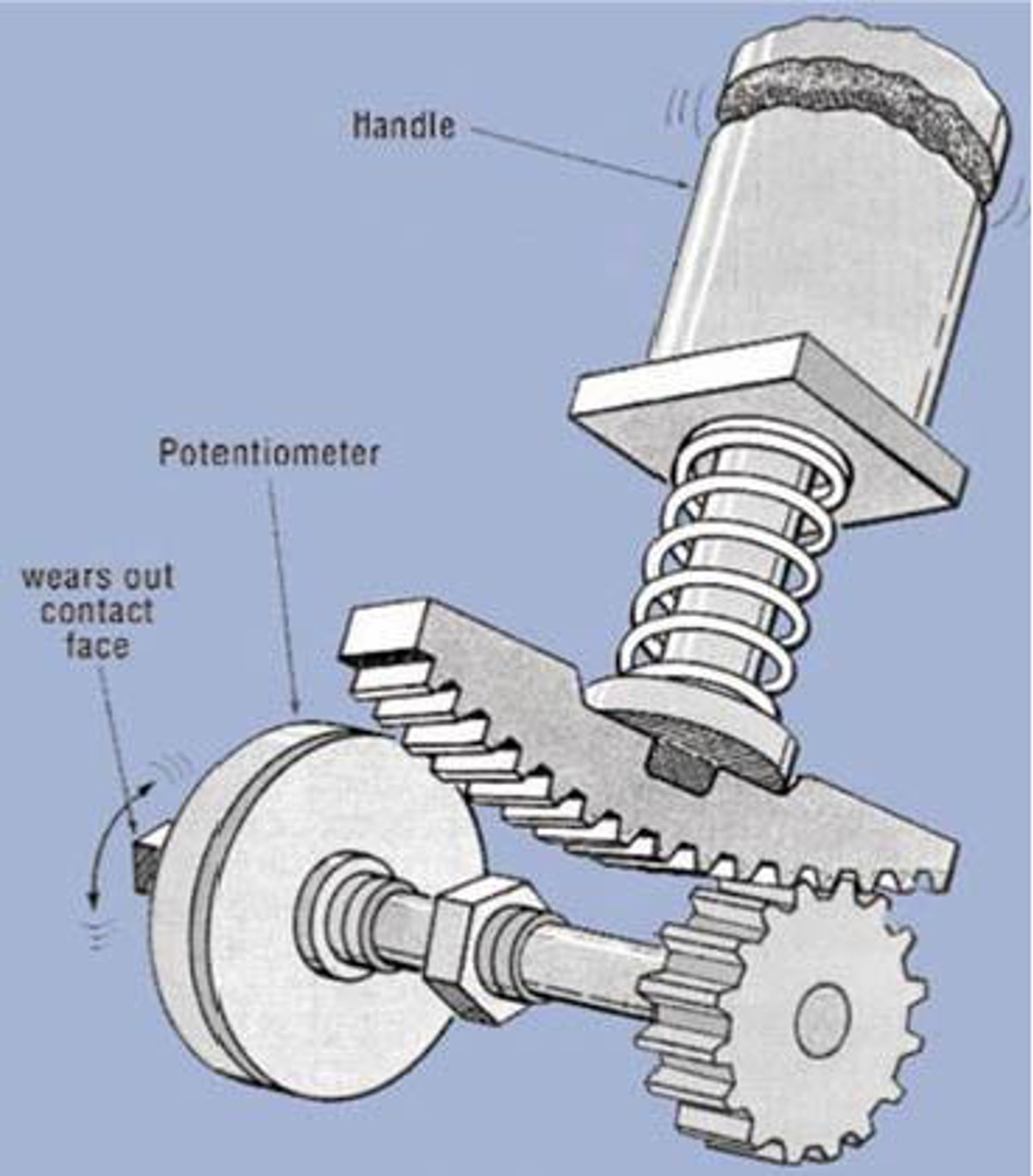

Our member conducted a full overhaul of the system but there were no obvious signs of damage or deterioration found. As a precaution to prevent further reoccurrences, the supplier of the jet drives was asked to attend the vessel the next day to perform a second system overhaul and fault finding exercise. After two further days of work on the system, the drive supplier concluded that a worn jet control potentiometer had caused the units not to respond as requested.

Incident 3 – Joystick potentiometer wear

This incident is similar to incident 2 above. Within the previous week on another crew transfer vessel the Master noticed the vessel was not steering correctly when on passage to site. Suddenly the steering on both units would not centralise and was stuck hard to starboard, the jet display alarmed with fault code: JS steer fault (joystick).

The Master, under advice over the phone from the superintendent, removed the joystick from the fly bridge steering console and replaced it with the faulty unit in the wheelhouse. All steering was regained. The faulty unit was sent back to the supplier, and under investigation it was found that the steering potentiometers had worn. Our member considered introducing planned maintenance/replacement of such units to prevent recurrence.

Related Safety Flashes

-

IMCA SF 17/13

29 November 2013

IMCA Safety Flashes summarise key safety matters and incidents, allowing lessons to be more easily learnt for the benefit of the entire offshore industry.

The effectiveness of the IMCA Safety Flash system depends on the industry sharing information and so avoiding repeat incidents. Incidents are classified according to IOGP's Life Saving Rules.

All information is anonymised or sanitised, as appropriate, and warnings for graphic content included where possible.

IMCA makes every effort to ensure both the accuracy and reliability of the information shared, but is not be liable for any guidance and/or recommendation and/or statement herein contained.

The information contained in this document does not fulfil or replace any individual's or Member's legal, regulatory or other duties or obligations in respect of their operations. Individuals and Members remain solely responsible for the safe, lawful and proper conduct of their operations.

Share your safety incidents with IMCA online. Sign-up to receive Safety Flashes straight to your email.