What have the alarms ever done for me?

- DP Event

- Published on 18 September 2023

- Generated on 22 February 2025

- DPE 03/23

- 4 minute read

Incident

Jump to:

A DP vessel with a two-way redundant split was in a blow off situation, even though environmental conditions at the time were marginal.

Overview

A DP vessel with a two-way redundant split was engaged in cargo operations alongside a fixed platform, the environmental conditions at the time were marginal however the vessel was in a blow off situation.

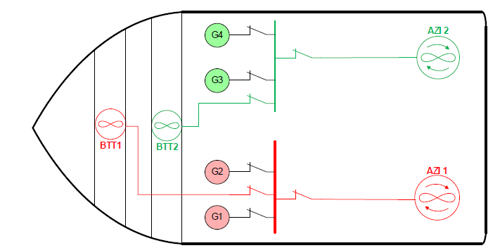

The vessel was operating in a split bus configuration, in this case a two-way split, each bus had two generators connected with each generator delivering approx. 40-50% power.

Figure one – Power Configuration Prior to Event

Not long into the operation alarms were activated on the vessels management system indicating that there was a low fuel pressure on the port fuel system, the alarms were accepted and cleared, however they became more frequent. The duty engineer called the bridge and enquired how long the operation would last, they were informed that there were only two lifts left. The decision was made to continue the cargo operation and investigate once the vessel had completed and moved out of the 500m Zone.

The alarms continued, however after a short time further alarms reported low frequency of both Bus sections along with dimming lights, shortly afterward the vessel blacked out.

At the time of the black out the vessel deck crew had just connected the last container to the rig crane, with the vessel in drift off and the marginal weather conditions, the vessel drifted rapidly causing the container to drag across the deck and snagging on the vessel sides before the rig crane operator attempted to lift the container clear. When the crane operator understood the situation, they tried to lift however due to the container snagging, the lifting strop failed.

The vessel was left blacked out and drifting uncomfortably beam onto the swell, it took over 30 minutes for the vessel crew to restore power and propulsion, in that time a lot of damage was inflicted on the vessel due to the uncomfortable motion.

What happened?

The vessel was operating open bus, it wouldn’t be unreasonable for the reader to assume all services were also split to provide independence and redundancy, and this was certainly what the vessel crew also assumed.

However, 24 hours earlier the vessel had a crew change, the off-signing crew failed to inform the on-signing crew that during their trip they had an issue with the starboard fuel system. The issue could not be immediately fixed as a part was required, so the vessels engineering staff cross connected the fuel systems forming a common system.

Figure two – Fuel system configuration at time of event

What can be concluded?

A number of conclusions can be drawn:

- No formal documenting of the issues with the fuel system

- No formal handover – the on signing crew unaware of changes, the crew change was literally a handshake due to travel arrangements.

- Field arrival Trials – are they suitable?

- Field arrival check lists – Did not pick up the cross connection.

- ASOG was effectively null void without the knowledge of the changes.

Management of change

There was a significant change of system operation for a major system. Why was this not formally captured and documented? The vessel owners were unaware that the starboard fuel system could not be configured independently, this defeated the redundancy concept of the vessel.

IMCA HSSE001 gives guidance on Management of Change.

Complacency

We must address the use of arrival/DP check lists. In this case the vessel had a comprehensive set of field/pre-DP checklists for both the bridge team and the engine room team. These checklists ask the user pertinent questions to assist in checking the status of the vessels redundancy and ability to survive a single point failure. Unfortunately, due to the repetitive nature of the process complacency can creep in and boxes are ‘ticked’ without a proper check.

Complacency is defined as a condition of being content with oneself or one’s circumstances, particularly when coupled by a lack of awareness of genuine threats or limitations. It can be risky since it causes people to become less cautious and more prone to making mistakes.

It is important to be aware of complacency and to take steps to avoid it. Complacency is a dangerous thing, but it is something that can be avoided. By being aware of complacency and by taking steps to avoid it, you can stay motivated and successful.

Latest DP incidents

-

Thorough preparation is key

With 4 of 8 diesel generators running and connected to a closed ring bus, and 7 of the 8 thrusters selected to DP, a DP equipment class 3 MODU was set up in Green mode whilst on standby.

DPE 03/24

5 November 2024

Incident

-

There – but not really there

This DP event occurred on a DP equipment class two supply vessel whilst carrying out cargo operations on the starboard side alongside the asset and working at the lee side in the drift-off position.

DPE 03/24

5 November 2024

Incident

-

Equipment Class 3, even if you operate as 'Class 2'

This case study examines a DP incident on an equipment class 3 multi-purpose vessel while operating in good conditions.

DPE 03/24

5 November 2024

Incident

-

Line of sight

This case study covers events onboard a DP equipment class 2 vessel whilst holding position in a turbine field, with three position reference systems selected into DP – DGPS, HPR and Fanbeam.

DPE 03/24

5 November 2024

Incident

-

DP Drill Scenario

DP emergency drill scenarios are included to assist DP vessel management, DPOs / Engineers, and ETOs in conducting DP drills onboard.

DPE 03/24

5 November 2024

Incident

The case studies and observations above have been compiled from information received by IMCA. All vessel, client, and operational data has been removed from the narrative to ensure anonymity. Case studies are not intended as guidance on the safe conduct of operations, but rather to assist vessel managers, DP operators, and technical crew.

IMCA makes every effort to ensure both the accuracy and reliability of the information, but it is not liable for any guidance and/or recommendation and/or statement herein contained.

Any queries should be directed to DP team at IMCA. Share your DP incidents with IMCA online. Sign-up to receive DP event bulletins straight to your email.